Women in Pharma: Connecting accessible pharma packaging to patients – a Pharmapack Special

.png)

Throughout our Women in Pharma series, we aim to highlight how CPHI events encourage discussions around diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in the pharmaceutical industry.

At Pharmapack 2025, held January 22-23, 2025 in Paris, France, we hosted a panel discussion on how pharmaceutical companies can integrate these values into practical actions surrounding packaging. Moderated by Elvire Regnier, Founder and President of Regenerative – Advisory, and featuring speakers Estelle Peyard, TechLab at APF France Handicap, Fatima Bennai-Sanfourche, Senior Director of QA & RA Compliance for Medical Devices and eHealth at Bayer AG, and Julian Dixon, Human Factors at Clarimed, the panel discussed how the pharmaceutical packaging industry plays a critical role in ensuring that patients of all abilities can access and use medications safely and effectively.

You can watch the full panel for free by registering here.

The panel kicked off with an introduction to the importance of considering accessible packaging, and how the industry must address the “innovation gaps” in healthcare. Peyard began by stating “When I interview others in the industry, I tell them that 40% of their clients may have disabilities, which represent a significant part of their potential clients. In the pharmaceutical industry, this percentage could even reach 100% even if they are temporary disabilities. A quick search on Google will show that pill packs for Parkinson's patients require the exact same dexterity as other types of packaging. Many patients need a nurse to come and help them take their medication. This isn’t just about patients with disability – sometimes the usability of medicines packaging is simply not adapted to the therapeutic applications.”

The history of patient advocacy in the pharmaceutical industry is nothing new, as Dixon pointed out when asked about what led to the rise of human factors in pharma by Regnier. “Human factors in the pharmaceutical industry started as advocacy groups from the early 1990s,” he answered. “All of that is really behind the FDA regulations for safety and medicine, and FDA regulation is what has driven human factor implementation in this place. By being part of the regulatory framework, you have this Faustian deal with the regulators – it's a good thing they are asking for all of these requirements, but it also makes processes quite restrictive... human factors has, in some ways, become imbalanced. It’s become a dominant thing in the regulatory framework, sometimes to a somewhat over-the-top degree. What we’re looking for here is balance, to make a better standard and more accessible platform, which would be wonderful. But this hasn’t happened yet. There are reasons why it hasn’t happened and there are reason why even now it is very hard for a standard to replace our current pre-filled syringe platforms.”

Building on an earlier presentation given by Regnier on working with suppliers to develop existing supply chains, Dixon called for efforts to be made around making existing packaging more accessible, a call that was echoed by the other panellists. “A pharmaceutical company is heavily involved in their supply chain systems,” Bennai-Sanfourche added. “With new drugs, what we have from the beginning are complex ecosystems because we need refill syringes for doses, digital tools for connectivity, cell and gene therapy tools – which require completely separate systems and supply chains – that need a lot of additional considerations. This complexity makes this difficult for all involved. It requires more testing and making sure that the end-user is able to use the drug that is sent to them... we also now have the ‘patient at home’ that is a lay-user that needs to operate many different parts of the medication, which was not the case before. This requires both the training and awareness on the patient’s end but also educating the healthcare provider that prescribes the medication, who may not be aware of the difficulties experienced by the patient population. How we make it more inclusive is the creation of these combined delivery systems of the drug and the device, and to have additional activities in our design process to ensure the performance of the delivery system, risk assessment, and how to make sure that the user can actually use it – this is the usability factor.”

Connecting patient, product, and industry

Connectivity was a key buzzword throughout the panel. Regnier drew on her experience in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and cosmetics sectors, commenting that suppliers are integral to approaching accessible packaging. However, such is not the case with pharma, she stated. In response, Bennai-Sanfourche explained that “For [pharma] there are rules and regulations we must follow. Packaging is not just to make a product look fancy – it is to protect the stability of the product in its lifecycle as well as to make sure the packaging is useful for users in their daily life... Because we are using medical devices and drug products together now, devices are a regulated product. That means we need to test it as well – it doesn’t make sense to have a delivery system that nobody can use.”

Peyard added that “We might have the most constraints compared to other industries, but we also have a great responsibility because some of the most vulnerable people will be using our products. Patients with problems with dexterity, or understanding labels, or concentration issues – these are all factors that can also be a source of creativity; it can really make for great innovation.”

Bennai-Sanfourche agreed. “All these constraints lead us to connectivity – connectivity of the device and drug to the patient when using their medication. Connectivity can really help a patient adhere to their prescription and help healthcare providers monitor the course of treatment. Sometimes, connectivity even means questioning the burden placed on the patient themselves. If the patient is unable to use new systems and not adhering to it, you must address this in your device design too.”

Connectivity wasn’t just used in relation to accessible drug delivery and devices – Peyard asked the panel to reflect on drug affordance, a concept she described as intuitive usage. “We describe it as the quality of a product that guides users on how to correctly use it – it is obvious and intuitive.” Bennai-Sanfourche stated that the complexity of some drug products often hinders the affordance of a delivery device. Dixon agreed, but gave some examples where such information could be intuitive. “If you look at the history of diabetes devices, it is amazing how the right affordances have won out. Pretty much all mainstream dialer dose pens have the same kind of interface. Similarly, the auto-injector has emerged with its own standard interface through this process of evolution. There’s only one thing to do with a two-step auto-injector, and that’s to pull the cap off and stab to deliver the medication.”

The challenge for Dixon, he stated, was how to bring about an ecosystem of change for complex platforms. Peyard responded that some innovations in fact came from patients themselves who struggled to use the devices for their medications, after which the industry adopted the platforms as standard. “That’s really the interesting part because that brings us to the important part of this discussion – you can innovate, but you must do it with the patients and the users.”

Related News

-

News US FDA adds haemodialysis bloodlines to devices shortage list

On March 14, 2025, the US FDA published an open letter to healthcare providers citing continuing supply disruptions of haemodialysis bloodlines, an essential component of dialysis machines. -

News Women in Pharma: Manufacturing personal and team success

Our monthly Women in Pharma series highlights the influential lives and works of impactful women working across the pharmaceutical industry, and how the industry can work towards making the healthcare industry and workplace more equitable and inclusive... -

News Pfizer may shift production back to US under Trump pharma tariffs

At the 45th TD Cowen annual healthcare conference in Boston, USA, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla outlined the potential for Pfizer to shift its overseas drug manufacturing back to the US as pharmaceutical industry players weigh their options against Presiden... -

News Experimental drug for managing aortic valve stenosis shows promise

The new small molecule drug ataciguat is garnering attention for its potential to manage aortic valve stenosis, which may prevent the need for surgery and significantly improve patient experience. -

News Vertex Pharmaceuticals stock jumps as FDA approves non-opioid painkiller

UK-based Vertex Pharmaceuticals saw their stock shares soar as the US FDA signed off on the non-opioid painkiller Journavx, also known as suzetrigine, for patients with moderate to severe acute pain, caused by surgery, accidents, or injuries. -

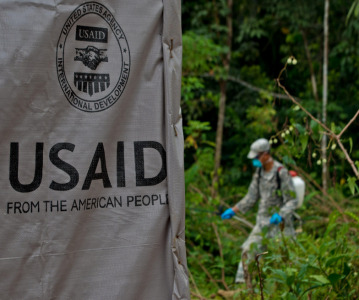

News Trump administration halts global supply of HIV, malaria, tuberculosis drugs

In various memos circulated to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Trump administration has demanded contractors and partners to immediately stop work in supplying lifesaving drugs for HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis to c... -

News 2024 Drug Approvals: a lexicon of notable drugs and clinical trials

50 drugs received FDA approval in 2024. The centre for biologics evaluation and research also identified six new Orphan drug approvals as under Biologics License Applications (BLAs). The following list picks out key approvals from the list, and highlig... -

News Medtech company Beta Bionics targets USD$616 million IPO valuation

California-based insulin delivery device manufacturer Beta Bionics have stated their intentions to target an IPO valuation of USD$616 million in the United States, signalling an optimistic recovery of medtech and biotech public listings.

Recently Visited

Position your company at the heart of the global Pharma industry with a CPHI Online membership

-

Your products and solutions visible to thousands of visitors within the largest Pharma marketplace

-

Generate high-quality, engaged leads for your business, all year round

-

Promote your business as the industry’s thought-leader by hosting your reports, brochures and videos within your profile

-

Your company’s profile boosted at all participating CPHI events

-

An easy-to-use platform with a detailed dashboard showing your leads and performance