Fighting cancer with the power of immunity

New treatment elicits two-pronged immune response that destroys tumors in mice.

Harnessing the body’s own immune system to destroy tumours is a tantalizing prospect that has yet to realize its full potential. A new advance from MIT, however, may bring this strategy, known as cancer immunotherapy, closer to becoming reality.

In the new study, the researchers used a combination of four different therapies to activate both of the immune system’s two branches, producing a coordinated attack that led to the complete disappearance of large, aggressive tumors in mice.

“We have shown that with the right combination of signals, the endogenous immune system can routinely overcome large immunosuppressive tumors, which was an unanswered question,” says Darrell Irvine, a professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

This approach, which could be used to target many different types of cancer, also allows the immune system to “remember” the target and destroy new cancer cells that appear after the original treatment.

Irvine and Dane Wittrup, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering and Bioengineering and a member of the Koch Institute, are the senior authors of the study, which appears in the 24 October online edition of Nature Medicine. The paper’s lead authors are MIT graduate student Kelly Moynihan and recent MIT PhD recipient Cary Opel.

Multipronged attack

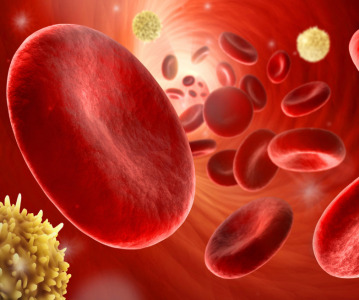

Tumour cells often secrete chemicals that suppress the immune system, making it difficult for the body to attack tumours on its own. To overcome that, scientists have been trying to find ways to provoke the immune system into action, with most focusing their efforts on one or the other of the two arms of immunity — the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

The innate system consists of nonspecific defenses such as antimicrobial peptides, inflammation-inducing molecules, and cells such as macrophages and natural killer cells. Scientists have tried to get this system to attack tumours by delivering antibodies that latch onto tumour cells and recruit the other cells and chemicals needed for a successful attack.

Last year, Wittrup showed that delivering antibodies and IL-2, a signaling molecule that helps to boost immune responses, could halt the growth of aggressive melanoma tumours in mice for as long as the treatment was given. However, this treatment worked much better when the researchers also delivered T cells along with their antibody-IL2 therapy. T cells — immune cells that are targeted to find and destroy a particular antigen — are key to the immune system’s second arm, the adaptive system.

Around the same time, Irvine’s lab developed a new type of T cell vaccine that hitches a ride to the lymph nodes by latching on to the protein albumin, found in the bloodstream. Once in the lymph nodes, these vaccines can stimulate production of huge numbers of T cells against the vaccine target.

After both of those studies came out, Irvine and Wittrup decided to see if combining their therapies might produce an even better response.

“We had this really good lymph-node-targeting vaccine that will drive very strong adaptive immunity, and they had this combination that was recruiting innate immunity very efficiently,” Irvine says. “We wondered if we could bring these two together and try to generate a more integrated immune response that would bring together all arms of the immune system against the tumour.”

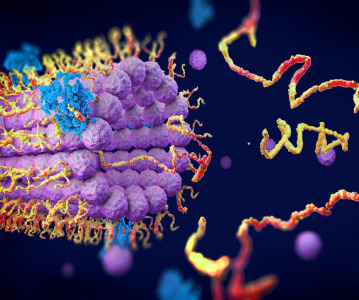

The resulting treatment consists of four parts: an antibody targeted to the tumour; a vaccine targeted to the tumour; IL-2; and a molecule that blocks PD1, a receptor found on T cells. Each of these molecules plays a critical role in enhancing the overall immune response to the tumour. Antibodies stimulate the recruitment of additional immune cells that help to activate T cells; the vaccine stimulates proliferation of T cells that can attack the tumour; IL-2 helps the T cell population to expand quickly; and the anti-PD1 molecule helps T cells stay active longer.

Tumour elimination

The researchers tested this combination treatment in mice that were implanted with three different types of tumours — melanoma, lymphoma, and breast cancer. These types of engineered tumours are much more difficult to treat than human tumours implanted in mice, because they suppress the immune response against them.

The researchers found that in all of these strains of mice, about 75% of the tumours were completely eliminated. Furthermore, 6 months later, the researchers injected tumour cells into the same mice and found that their immune systems were able to completely clear the tumour cells.

“To our knowledge, nobody has been able to take tumours that big and cure them with a therapy consisting entirely of injecting biomolecular drugs instead of transplanting T cells,” Wittrup says.

Using this approach as a template, researchers could substitute other types of antibodies and vaccines to target different tumors. Another possibility that Irvine’s lab is working on is developing treatments that could be used against tumours even when scientists don’t know of a specific vaccine target for that type of tumour.

Related News

-

News Google-backed start-up raises US$600 million to support AI drug discovery and design

London-based Isomorphic Labs, an AI-driven drug design and development start-up backed by Google’s AI research lab DeepMind, has raised US$600 million in its first external funding round by Thrive Capital. The funding will provide further power t... -

News AstraZeneca to invest US$2.5 billion in Beijing R&D centre

Amid investigations of former AstraZeneca China head Leon Wang in 2024, AstraZeneca have outlined plans to establish its sixth global strategic R&D centre in China. Their aim is to further advance life sciences in China with major research and manufact... -

News Experimental drug for managing aortic valve stenosis shows promise

The new small molecule drug ataciguat is garnering attention for its potential to manage aortic valve stenosis, which may prevent the need for surgery and significantly improve patient experience. -

News How GLP-1 agonists are reshaping drug delivery innovations

GLP-1 agonist drug products like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro have taken the healthcare industry by storm in recent years. Originally conceived as treatment for Type 2 diabetes, the weight-loss effects of these products have taken on unprecedented int... -

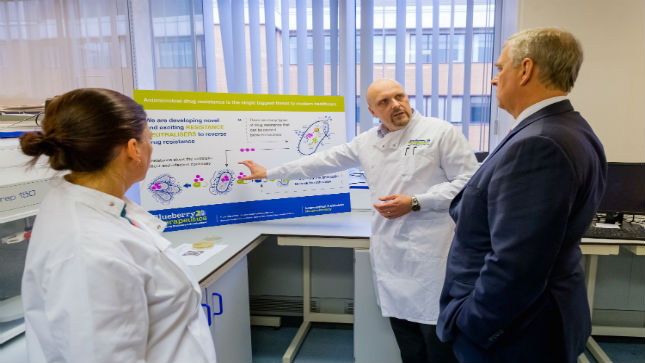

News A Day in the Life of a Start-Up Founder and CEO

At CPHI we work to support Start-Up companies in the pharmaceutical industry and recognise the expertise and innovative angles they bring to the field. Through our Start-Up Programme we have gotten to know some of these leaders, and in this Day in the ... -

News Biopharmaceutical manufacturing boost part of new UK government budget

In their national budget announced by the UK Labour Party, biopharmaceutical production and manufacturing are set to receive a significant boost in capital grants through the Life Sciences Innovative Manufacturing Fund (LSIMF). -

News CPHI Podcast Series: The power of proteins in antibody drug development

In the latest episode of the CPHI Podcast Series, Lucy Chard is joined by Thomas Cornell from Abzena to discuss protein engineering for drug design and development. -

News Amgen sues Samsung biologics unit over biosimilar for bone disease

Samsung Bioepis, the biologics unit of Samsung, has been issued a lawsuit brought forth by Amgen over proposed biosimilars of Amgen’s bone drugs Prolia and Xgeva.

Recently Visited

Position your company at the heart of the global Pharma industry with a CPHI Online membership

-

Your products and solutions visible to thousands of visitors within the largest Pharma marketplace

-

Generate high-quality, engaged leads for your business, all year round

-

Promote your business as the industry’s thought-leader by hosting your reports, brochures and videos within your profile

-

Your company’s profile boosted at all participating CPHI events

-

An easy-to-use platform with a detailed dashboard showing your leads and performance

.png)